Funded project

I moved back to the Baltics with an ambition to continue making yurts, a craft which I learned while living in England. I did work with a traditional English wood craftsman Glen, who made a coppiced hazel frame for the shelter and I was a seamstress (link for visual examples) who was responsible for sewing covers individually fitted to each yurt carcass. This is what I wanted to continue doing upon my return to Latvia. I inherited woodland from my grandparents with hazel growth and knowledge from Glen about hazel coppicing and processing. It seems that I am all set for the yurt-making business; still and all, using cordura fabric for cover felt unnatural, as I learned about micro-plastic pollution from synthetic fibre textiles. Reading about river Tame in Greater Manchester, my home for 16 years is a most polluted river in whole United Kingdom; and understanding how micro-plastic water contamination happens: even though waste water companies are blamed for it, we must understand that in first place micro-plastics comes from domestic everyday use of textiles made of synthetic fibres… fast forwarding my chain of thoughts I started questioning ethics of using cordura for yurt making as it does deteriorate over time and plastic slowly seeps into a ground where yurt is standing (plus such portable structures are advisable to use in nature parks as they have minimal ground disturbance also do not need planning permission). Therefore I put my plans of yurt production in Latvia on hold until I will figure out a way to source a biodegradable, natural fibre material for outdoor use in such weather conditions as in Baltic countries.

As I journeyed further in my search for the weather-proof, natural yurt cover fabric I realised Latvian fabric production is no longer existent, we produce only raw fibre, which is we just farm for some linen, hemp, wool fibres… plus we have adapted a industrial monoculture farming style, which is not sustainable. I did come to a point where I realised I will have to start all from the very beginning, retrace the steps of my ancestors and learn how to make my own fabric if I want to create something which is ethically produced from seed to the finished product. And by ethical I mean regenerative, as this term describes a process making something out of natural materials but in the way it not just replaces them but regenerates nature and with practice of regenerative farming, one is able to reverse damage done to the ecology by industrial farming.

One could say it is returning back to the basics, but we are armed with information technology now to be able to make informed decisions on how to do things right. And the basis for natural textiles are simple: it’s farming and it uses the same techniques as food farming (agriculture, husbandry, it is supposed to be a land care for human benefit). Most well known plant textile fibres of the Baltic region are linen and hemp, and animal: wool. And these natural fibres I’d like to investigate as potential materials for making yurt covers.

Place where I am from Latgale, has deep soils ideal for farming linen and hemp. However materials used in traditional Mongolian or Siberian yurts are wool or animal skins. I could not imagine myself de-skinning an animal, even though this could provide an instant insulated waterproof cover for shelter. I did find that it is possible to make leather substitutes from mycelium, but that is lab-work and not something I could just grow on the open field integrated into a biosphere of local nature. So I laid my eyes on ‘wool’.

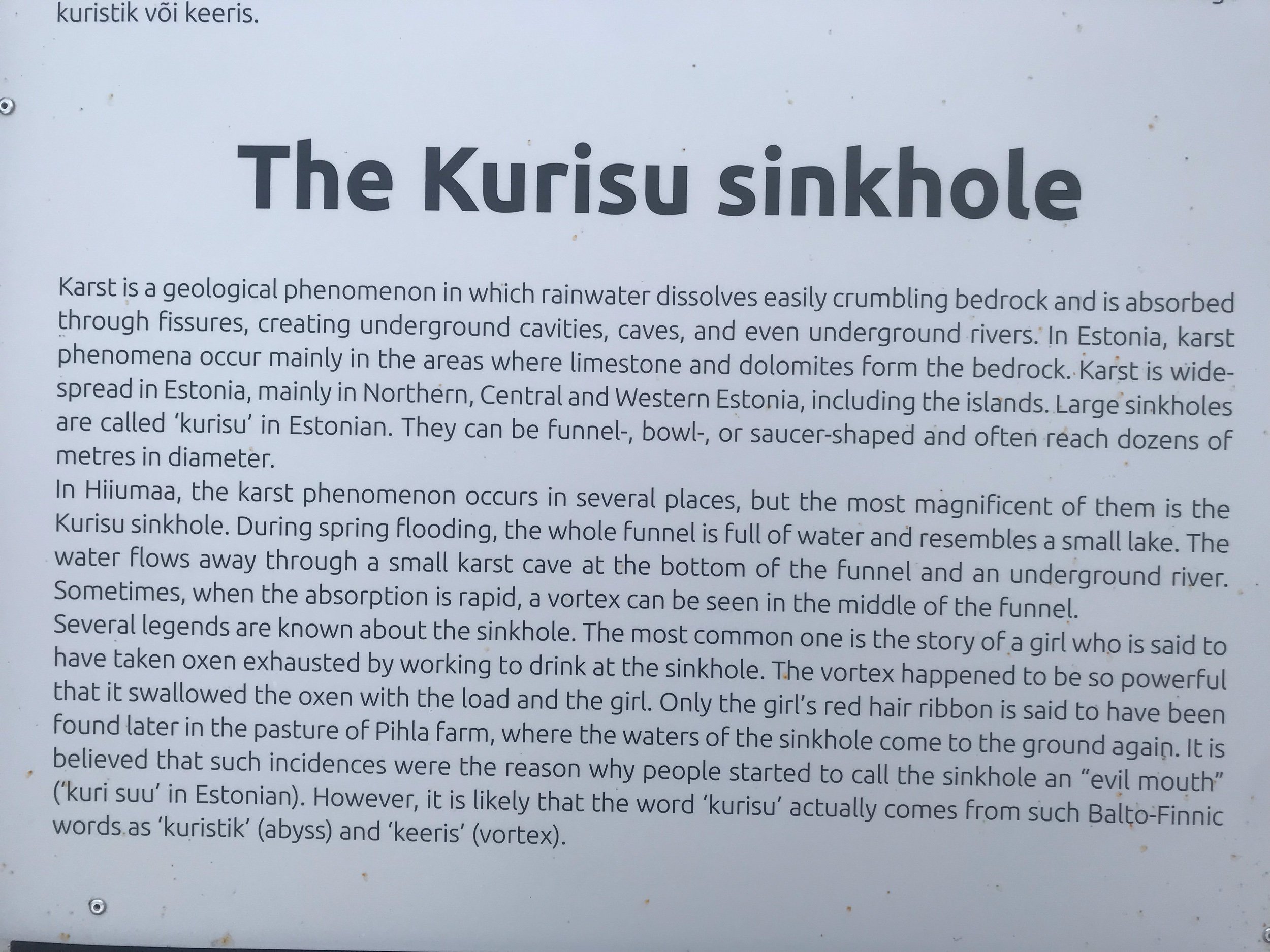

Summer 2020, I was fortunate to venture onto Hiiumaa (can follow the link to see my first travels to the island) in Estonia where I met with a sheep farmer Merike. She raises sheep for wool and sells it to the local wool factory. But this is the main goal for having sheep. Merike acquired first sheep as companion animals as she retired and moved to live on her parents small farm-house about two decades ago. She is integrated into her homesteading: they eat the grass of fields helping to maintain meadows, at night and during winter sheep live in a stable, this is where a manure is created (balancing hay as carbon with sheep poop and urine as nitrogen for creating nutrient-rich compost) for the use onto a vegetable garden. Care for sheep also supports mental health as it provides a meaningful daily routine for Merike and happiness receiving new lambs and watching them grow. Some of the sheep do get killed and became food, it might sound cruel but this is part of the no waist life cycle of a farm and contributes to local economy as an export from the island, as shallow and boggy soils of Hiiumaa does not allow for large scale plant production (which any case now is proven to be unsustainable and detrimental to the soils’ health), raising animals for me does make ecological sense here.

My main goal for the stay at the farm was to learn about wool for textiles, including how to look after sheep during winter when snow has covered grazing meadows and animals have to stay indoors fed with hay. And what jobs can be done to prepare wool as sheep get sheared in autumn. I imagined that it could be washed during this period as it’s best cleaned in rain water or melted snow for softness. However in Merike’s farm wool drying happens outside and it’s not possible in the month of February when I arrived. I imagined that I would be able to felt using raw wool but this was not the case. Regardless, Merike has something much better planned for me to learn during my stay: traditional Estonian weaving on horizontal loom.

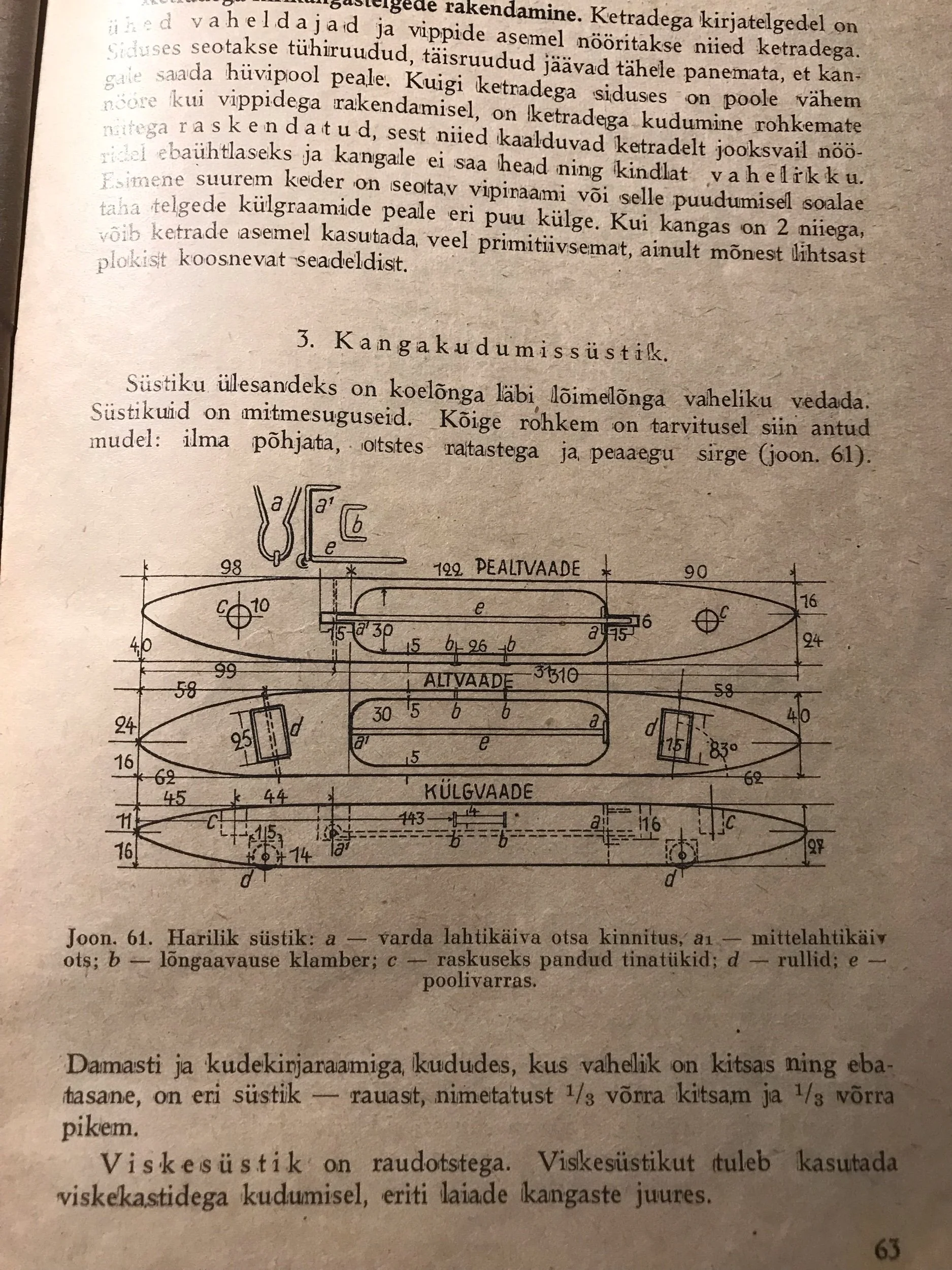

At Merike’s house was her mother’s loom from 1919. It had not been used for more than 20 years since her mother fell ill. Loom was partly dismantled. Merike had not learned the weaving craft from her mother, she invited a couple local weaving masters to help us to set up a loom and teach me the basics of how to use it. Ladies were excited to teach and pass on the craft, same as me to be able to understand how to set up such a machine, and use it. It felt as understanding history through the handicraft, imagining how it felt like to place a line upon a line of wool for hours during dark winters in between morning and evening trips to the stable to feed the sheep who’s wool by now has been processed and made into threads. (I used wool threads processed at the local HiiuVill factory and some which I saved from my grandma’s dowry); learned the natural wool dyeing process and principles of making a cloth.

What took me by surprise was that the threads for the weaving’s base were linen! It gave a kinda tangible, symbolic sense to my travels between Latgale and Hiiumaa, the idea that in order to create a fabric for the yurts I could use wool from Hiiumaa and plant fibres like linen from Latgale combined is a logical way to pursue my quest.

So it happen that just before setting of to spend time at Merike’s farm I visited Grand Canyon and New York. Journey felt somehow connected only if through my personal experience and interpretation. Place like Amerika so far removed from traditional innate knowledge of crafts as human connection to the nature and which now theoretizes on reviving indigenous practices of farming and invented a notion of regenerative agriculture. It did made me think weather we in Baltics could learn from mistakes done in US industrial farming and skip process of damaging our soils to revive and conserve our ways of natural (pre-soviet) farming. We might be considered to be behind in economical development but maybe we can skip this step and be further in sustainable or regenerative agriculture practice?

At night upon my arrival at Merike’s farm two black lambs were born. I could witness how to take care of sheep from very first days of their life.

Every morning and evening sheep were given water (best if it was rain-water mixed with hot) and hay. Being at the farm came handy for Merike as the biggest challenge over winter is to unpack hay rolls and pull them under the roof so they don’t root and turn into mushroom food. For a 74 year-old lady this can be a big challenge: help is essential. One sheep eats over a roll of hay during winter therefore at least 30 are needed at the farm. We humans were an essential part of the circular system here: pulling hay in, then sheep them all turning it into poop which mixed with hay again gets pulled out the sheep shed into a nearby veggie garden as manure. And sheep themselves are growing wool on their shoulders which eventually becomes jumpers on our shoulders.

Between the 4 of us we managed to set up Merike’s mum’s loom and it was in working condition. I had 10mt of linen base thread set up for me to weave 10mt of fabric or traditional rug in a simple style where I could only make different color line patterns alternating. For that I had prepared few dyed wools: soaked in melted snow and white vinegar, shades of yellow gained from turmeric and masala spices which were eaten by Tineola Bisselliella known as cloth moth, who would happily eat anything woolen for that reason strong-smelling soap, thyme or lavender, including wormwood, mint, St. John's wort or Rhododendron Tomentosum (marsh Labrador tea, vaivariņš) easily collectable in Hiiumaa bogs.

On the walks around the village I kept an eye on local wooden architecture and was especially pleased to find a cold store overgrown with hazel. It was done purposely so roots keep the soil mound in place (a cold-store is buried under soil so it does not freeze in winter and in summer keep it cool). Hazel was coppiced, which prolongs its roots life, and poles were used as fencing to make kinda balconies with more soil, I wondered if they are beds for plants to grow. It was hard to tell in February, but something to come back to and observe in spring!

…drawing of natural building using poles of hazel or willow.

Living within a natural system, can be felt when getting manure out from a sheep shed into a garden, and then having a traditional sauna!